Bucharest has two famous 19th century passageways, running off Calea Victoriei eastwards, Pasajul Victioriei and Pasajul Vilacrosse. I walk down both often. The latter is now full of bars and fun. It has a third one, much more secret, called Pasajul Englez.

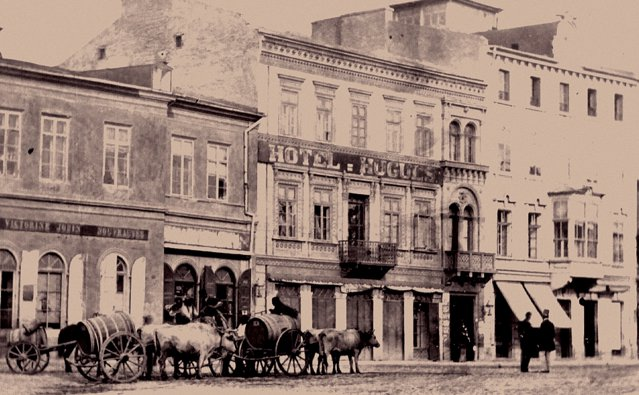

The jeweller Joseph Resch, whose shop was nearby, built a narrow house opposite what became the National Theatre, where Novotel is. The facade of Novotel is a copy of the facade of the National Theatre, which was destroyed by German bombs in 1944 (not British bombs, as I long thought). The house was bought in 1885 and transformed into first hughes Hotel, then the English Hotel. The English Passage, which connects Calea Victoriei with Strada Academiei, was built then, the hotel bedrooms lining the narrow passage.

The writer Mateiu Caragiale writes about Pasjul Englez in his Rakes of the Old Court, a book that is on my coffee table waiting to be read.

I found this description on an interesting site, with much curious information about Calea Victoriei. I do not know when this was written- not in the last many years. It reminds me of Lawrence Durrell.

Today, the passage is difficult to find, either from Calea Victoriei or from Calea Academiei, because the entrances are hidden by filth in plain sight. You can still see the balconies where the pleasure sellers used to be exposed. But the building, although classified as a historical monument, is dilapidated and totally unmaintained. The rust-eaten metal balconies are about to collapse.

The English Passage has been used for various films, including Cuibul de Viespi directed by Horea Popescu and Dracula II: Ascension directed by Patrick Lussier, as well as in a video by the Romanian soloist Alex.

A low passage leads to a place where at least the girls have nothing to look for. Darkness, aggressive smell of urine and other nauseous waste, then you catch sight of a bouncer who sits like an emperor on the birt on the left and stares at you. If you manage to look up, you say you're in prison (one like in season 3 of "Prison Break", Panama). From the unsanitary and rickety balconies, voices are heard raised in argument, but you see no one. You quickly look down, so as not to be suspected of being likely to cause trouble.

If by "Tales of the Old Court" is meant "Craii de Curtea-Veche" then it is by Mateiu Caragiale, the son of the famous Caragiale (Ion Luca). Though Mateiu is famous is his own right. ("Ion Luca Caragiale" and "biserica catolică", the only two tolerated cacophonies of the Romanian language, I've been told.)

ReplyDeleteNote the spelling: Mateiu with a final 'u'. I've been told that it was silent, so the pronounciation should be the same as today's "Matei".

The original title contains "craii" (the articulated plural of "crai"). "Crai" has either Hungarian etymology (from "kiraly", king) or Slavic ("krali", also king). Both seem to stem from "Carolus/Karl", by which is meant Charlemagne. Nowadays the word is used in Romanian to designate a womaniser. I've checked the dictionary and it is even harsher: "Crai de Curtea veche = derbedeu, desfrânat, haimana, pungaș".

I've been fascinated with the capacity of Romanians to turn the meaning of imported words into farce. From "king" to "womanizer". I heard "zdreanță" means "handkerchief" in Russian, but I can find no reference. It became "rag" in Romanian. "Nauka" means science in Russian or various Slavic languages. It gave "năuc" in Romanian which means "crazy", "not sound in his head". "Rahat" has very positive conotations in Turkish. It means "comfort", "comfortable", but also "luxurious", metaphorically "sweet". You know what it ended up meaning in Romanian.

Thank you very much for the correction - of course I meant Caragiale the younger, but wrote hastily.

DeleteThere are 3 tolerated cacophonies in Romanian language, the 3rd one being "tactica cavalereasca" which means "chivalric tactics"

ReplyDelete